Renaissance - VII

Titian

c. 1488/90 – 1576

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (c. 1488/90 – 27 August 1576), Latinized as Titianus, hence known in English as Titian Renaissance painter of Lombard origin, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno. During his lifetime he was often called da Cadore, 'from Cadore', taken from his native region.

Recognized by his contemporaries as "The Sun Amidst Small Stars" (recalling the final line of Dante's Paradiso), Titian was one of the most versatile of Italian painters, equally adept with portraits, landscape backgrounds, and mythological and religious subjects. His painting methods, particularly in the application and use of colour, exerted a profound influence not only on painters of the late Italian Renaissance, but on future generations of Western artists.

His career was successful from the start, and he became sought after by patrons, initially from Venice and its possessions, then joined by the north Italian princes, and finally the Habsburgs and papacy. Along with Giorgione, he is considered a founder of the Venetian school of Italian Renaissance painting.

During the course of his long life, Titian's artistic manner changed drastically, but he retained a lifelong interest in colour. Although his mature works may not contain the vivid, luminous tints of his early pieces, they are renowned for their loose brushwork and subtlety of tone.

Self-portrait of the Italian painter Tiziano Vecellio (c. 1490-1576), better known as Titian.

Christ Carrying the Cross

1506-07

The Holy Family with a Shepherd

c. 1510

Christ Carrying the Cross

1506-07

Noli me tangere

1511-12

Madonna and Child with Sts Catherine and Dominic and a Donor

1512-16

The Miracle of the Jealous Husband

1511

The Tribute Money

1516

Madonna and Child with St Catherine and a Rabbit

1530

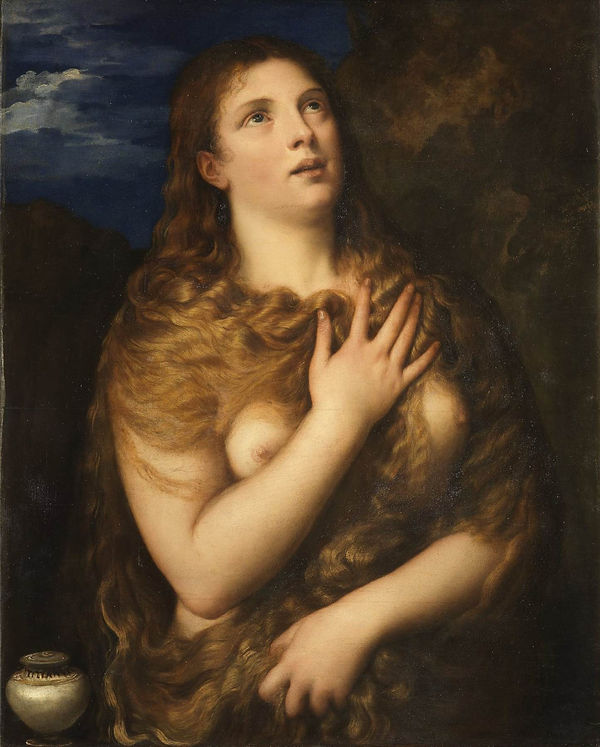

The Penitent Magdalene

c. 1532

Virgin and Child

c. 1545

Ecce Homo

1548

Adam and Eve

c. 1550

Penitent St Mary Magdalene

c. 1565

Pietà

1576

Sacred and Profane Love

1514

Venus Anadyomene

c. 1520

Venus of Urbino

1538

Tityus

1548-49

Venus with Organist and Cupid

1548

Venus and Cupid with an Organist

1548-49

Venus and an Organist and a Little Dog

c. 1550

Danaë

c. 1553

Jupiter and Antiope (Pardo Venus)

1535-40, reworked c. 1560

Venus and Cupid

c. 1550

Venus with a Mirror

c. 1555

Venus and Adonis

1550s

Venus Blindfolding Cupid

c. 1565

The Flaying of Marsyas

1576

Bacchus and Ariadne

1520-22

Diana and Actaeon

1556-59

Diana and Callisto

1556-59

Rape of Europa

1559-62

Death of Actaeon

1562

Tarquin and Lucretia

1568-71

Young Woman with a Dish of Fruit

c. 1555

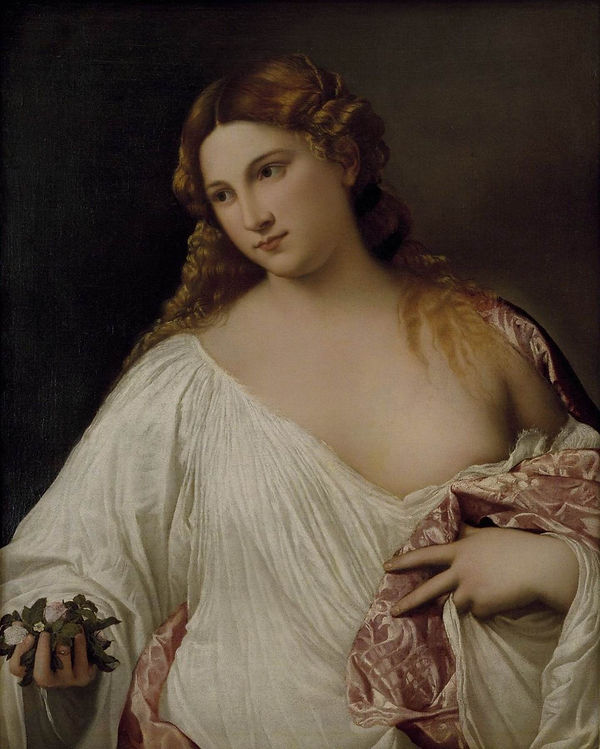

Flora

1515-20

Judith

c. 1515

Pope Paul III with his Grandsons Alessandro and Ottavio Farnese

1546

Correggio

1489 – 1534

Antonio Allegri da Correggio (August 1489 – 5 March 1534), usually known as just Correggio, was the foremost painter of the Parma school of the High Italian Renaissance, who was responsible for some of the most vigorous and sensuous works of the sixteenth century. In his use of dynamic composition, illusionistic perspective and dramatic foreshortening, Correggio prefigured the Baroque art of the seventeenth century and the Rococo art of the eighteenth century. He is considered a master of chiaroscuro.

Antonio Allegri was born in Correggio, a small town near Reggio Emilia. His date of birth is uncertain (around 1489). His father was a merchant. Otherwise little is known about Correggio's early life or training. It is, however, often assumed that he had his first artistic education from his father's brother, the painter Lorenzo Allegri.

In 1503–1505, he was apprenticed to Francesco Bianchi Ferrara in Modena, where he probably became familiar with the classicism of artists like Lorenzo Costa and Francesco Francia, evidence of which can be found in his first works. After a trip to Mantua in 1506, he returned to Correggio, where he stayed until 1510. To this period is assigned the Adoration of the Child with St. Elizabeth and John, which shows clear influences from Costa and Mantegna. In 1514, he probably finished three tondos for the entrance of the church of Sant'Andrea in Mantua, and then returned to Correggio, where, as an independent and increasingly renowned artist, he signed a contract for the Madonna altarpiece in the local monastery of St. Francis (now in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie).

One of his sons, Pomponio Allegri, became an undistinguished painter. Both father and son occasionally referred to themselves using the Latinized form of the family name, Laeti.

The Adoration of the Child

1518-20

Madonna of the Basket

c. 1524

Madonna and Child with Sts Jerome and Mary Magdalen (The Day)

1525-28

Virgin and Child with an Angel (Madonna del Latte)

1522-25

Madonna with St George

1530-32

Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John

1516

Nativity (Holy Night)

1528-30

Allegory of Virtues

1525-30

Allegory of Vices

1525-30

The Education of Cupid

about. 1528

Danaë

1530

Ganymede

1531-32

Leda with the Swan

1531-32

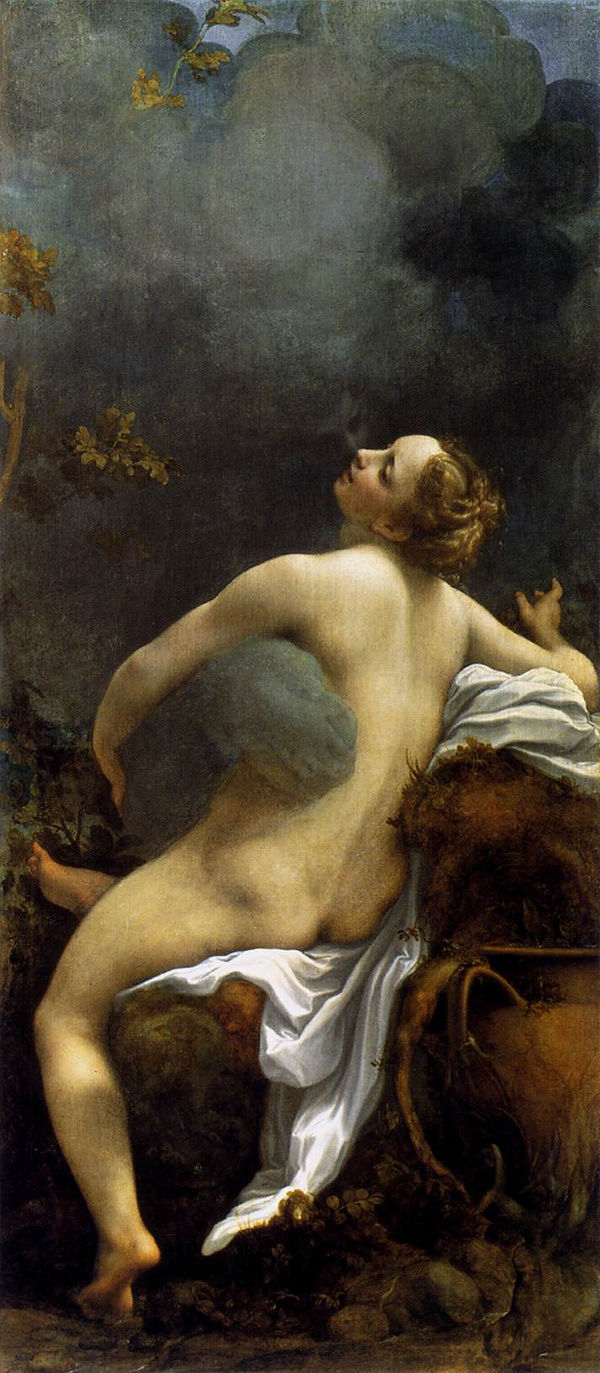

Jupiter and Io

1531-32

Venus and Cupid with a Satyr

1524-25

Deposition from the Cross

1525

Ecce Homo

The Mystic Marriage of St Catherine

1526-27

Portrait of a Gentlewoman

1517-19

Dosso Dossi

1489–1542

Self-portrait

Giovanni di Niccolò de Luteri, better known as Dosso Dossi (c. 1489–1542), was an Italian Renaissance painter who belonged to the School of Ferrara, painting in a style mainly influenced by Venetian painting, in particular Giorgione and early Titian.

From 1514 to his death he was court artist to the Este Dukes of Ferrara and of Modena, whose small court valued its reputation as an artistic centre. He often worked with his younger brother Battista Dossi, who had worked under Raphael. He painted many mythological subjects and allegories with a rather dream-like atmospheres, and often striking disharmonies in colour. His portraits also often show rather unusual poses or expressions for works originating in a court.

Dossi was born in San Giovanni del Dosso, a village in the province of Mantua. His early training and life are not well documented; his father, originally of Trento, was a bursar (spenditore or fattore) for the Dukes of Ferrara. He may have had training locally with Lorenzo Costa or in Mantua, where he is known to have been in 1512. By 1514, he would begin three decades of service for dukes Alfonso I and Ercole II d'Este, becoming principal court artist. Dosso worked frequently with his brother Battista Dossi, who had trained in the Roman workshop of Raphael. The works he produced for the dukes included the ephemeral decorations of furniture and theater sets. He is known to have worked alongside il Garofalo in the Costabili polyptych. One of his pupils was Giovanni Francesco Surchi (il Dielai).

Dosso Dossi is known less for his naturalism or attention to design, and more for cryptic allegorical conceits in paintings around mythological themes, a favored subject for the humanist Ferrarese court (see also Cosimo Tura and the decoration of the Palazzo Schifanoia). Dossi employed eccentric distortions of proportion, which may appear caricature-like or even 'primitivist'. The art historian Sydney J. Freedberg sees this characteristic as an expression of the Renaissance aesthetic of sprezzatura (i.e. "studied carelessness", or artistic nonchalance). Dossi is also known for the atypical choices of bright pigment for his cabinet pieces. Some of his works, such as the Deposition have lambent qualities that suggest some of Correggio's works. Most of his works feature Christian and Ancient Greek themes and use oil painting as a medium.

The painting Aeneas in the Elysian Fields was part of the Camerino d'Alabastro of Alfonso I in the Este Castle, decorated with canvases depicting bacchanalia and erotic subjects including Feast of the Gods by Giovanni Bellini and Venus Worship by Titian. The frieze paintings were based on the Aeneid; this scene by Dossi is book 6, lines 635–709, wherein Aeneas is guided over the bridge into the Elysian Fields by the Cumaean Sibyl. Orpheus with the lyre flits in the forest; in the background are the ghostly horses of dead warriors.

In Hercules and the Pygmies, Hercules has fallen asleep after defeating Antaeus, and is set upon by an army of thumb-size pygmies, whom he defeats. He gathers them in his lion skin. Paintings depicting a powerful Hercules were commonly made for the then-ruler Duke Ercole II d'Este. The subjects of the Mythological Scene and Tubalcain are unknown.

Recently, "Portrait of a Youth" at the National Gallery of Victoria, has been identified by the museum as a portrait of Lucrezia Borgia by Dosso Dossi, having previously been regarded as the portrait of an unknown young male by an unknown painter.

Bacchus

c. 1524

Circe and her Lovers in a Landscape

1514-16

Circe

c. 1520

Madonna and Child with Sts John the Baptist and Jerome

1517-19

Diana and Calisto

c. 1528

The Embrace

1526-28

The Holy Family

1527-28

Jupiter, Mercury and the Virtue

1515-18

Jupiter and Semele

1520s

Madonna and Child

c. 1525

Allegory of Music

c 1522

Nymph and Satyr

1510-16

St Sebastian

Sibyl

1524-25

Anger or the Tussle

1515-16

Portrait of a Warrior

1530s

Witchcraft (Allegory of Hercules)

1540-42

Portrait of a Youth, now claimed to be a portrait of Lucrezia Borgia

1518

Pontormo

1494 – 1557

Jacopo Carucci or Carrucci (May 24, 1494 – January 2, 1557), usually known as Jacopo (da) Pontormo or simply Pontormo (IPA: [ponˈtormo]), was an Italian Mannerist painter and portraitist from the Florentine School. His work represents a profound stylistic shift from the calm perspectival regularity that characterized the art of the Florentine Renaissance. He is famous for his use of twining poses, coupled with ambiguous perspective; his figures often seem to float in an uncertain environment, unhampered by the forces of gravity.

Jacopo Carucci was born at Pontorme (then known as Pontormo or Puntormo), near Empoli, to Bartolomeo di Jacopo di Martino Carrucci and Alessandra di Pasquale di Zanobi. Vasari relates how the orphaned boy, "young, melancholy, and lonely", was shuttled around as a young apprentice:

Jacopo had not been many months in Florence before Bernardo Vettori sent him to stay with Leonardo da Vinci, and then with Mariotto Albertinelli, Piero di Cosimo, and finally, in 1512, with Andrea del Sarto, with whom he did not remain long, for after he had done the cartoons for the arch of the Servites, it does not seem that Andrea bore him any good will, whatever the cause may have been.

Illustratio from "Le Vite" by Giorgio Vasari, edition of 1568

Leda and the Swan

1512-13

Lady with a Basket of Spindles

c. 1516

Madonna and Child with St. Joseph and Saint John the Baptist

1521-27

Madonna and Child with the Young St John the Baptist

1520-25

Visitation

1528-29

Madonna and Child with the Young St John

1529-30

Portrait of a Lady in Red

1530s

The Expulsion from Earthly Paradise

c. 1535

Maria Salviati with Giulia de' Medici

c. 1537

Portrait of Maria Salviati

1537-43

Venus and Cupid

1532-34

Deposition

c. 1528

Lunette fresco

1519-21

Villa Medici, Poggio a Caiano

Lunette fresco (detail)

1519-21

Villa Medici, Poggio a Caiano

Lunette fresco (detail)

1519-21

Villa Medici, Poggio a Caiano

Lunette fresco (detail)

1519-21

Villa Medici, Poggio a Caiano

Lunette fresco (detail)

1519-21

Villa Medici, Poggio a Caiano

Rosso Fiorentino

1495 – 1540

Plate of "Il Rosso", from Le vite de’ piv eccellenti pittori, scvltori, e architettori (Fiorenza: Appresso i Giunti, 1568), by Giorgio Vasari

Giovanni Battista di Jacopo (8 March 1495 in Gregorian style, or 1494 according to the calculation of times in Florence where the year began on 25 March - 14 November 1540), known as Rosso Fiorentino (meaning "Red Florentine" in Italian), or Il Rosso, was an Italian Mannerist painter who worked in oil and fresco and belonged to the Florentine school.

Born in Florence with the red hair that gave him his nickname, Rosso first trained in the studio of Andrea del Sarto alongside his contemporary, Pontormo. His early works include Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist (Walters Art Gallery), Cherub Playing a Lute (Uffizi) and The Infant Saint John the Baptist (private collection), all produced around 1521. In late 1523, Rosso moved to Rome, where he was exposed to the works of Michelangelo, Raphael, and other Renaissance artists, resulting in the realignment of his artistic style.

Fleeing Rome after the Sacking of 1527, Rosso eventually went to France where he secured a position at the court of Francis I in 1530, remaining there until his death. Together with Francesco Primaticcio, Rosso was one of the leading artists to work at the Chateau Fontainebleau as part of the "First School of Fontainebleau", spending much of his life there. Following his death in 1540 (which, according to an unsubstantiated claim by Vasari, was a suicide), Francesco Primaticcio took charge of the artistic direction at Fontainebleau.

Rosso's reputation, along those of other stylized late Renaissance Florentines, was long out of favour in comparison to other more naturalistic and graceful contemporaries, but has revived considerably in recent decades. That his masterpiece is in a small city, away from the tourist track, was a factor in this, especially before the arrival of photography. His poses are certainly contorted, and his figures often appear haggard and thin, but his work has considerable power.

Madonna and Child with Putti

c. 1522

A Young Man

1517-18

Madonna Enthroned with Four Saints

1518

Musician Angel

1521

Descent from the Cross

1521

Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro

1523-24

Dead Christ with Angels

1525-26

Pietà

1537-40

Bacchus, Venus and Cupid

(c. 1531)

Hans Holbein the Younger

c. 1497—1543

Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497 – between 7 October and 29 November 1543) was a German-Swiss painter and printmaker who worked in a Northern Renaissance style, and is considered one of the greatest portraitists of the 16th century. He also produced religious art, satire, and Reformation propaganda, and he made a significant contribution to the history of book design. He is called "the Younger" to distinguish him from his father Hans Holbein the Elder, an accomplished painter of the Late Gothic school.

Holbein was born in Augsburg but worked mainly in Basel as a young artist. At first, he painted murals and religious works, and designed stained glass windows and illustrations for books from the printer Johann Froben. He also painted an occasional portrait, making his international mark with portraits of humanist Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam. When the Reformation reached Basel, Holbein worked for reformist clients while continuing to serve traditional religious patrons. His Late Gothic style was enriched by artistic trends in Italy, France, and the Netherlands, as well as by Renaissance humanism. The result was a combined aesthetic uniquely his own.

Holbein travelled to England in 1526 in search of work with a recommendation from Erasmus. He was welcomed into the humanist circle of Thomas More, where he quickly built a high reputation. He returned to Basel for four years, then resumed his career in England in 1532 under the patronage of Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell. By 1535, he was King's Painter to Henry VIII of England. In this role, he produced portraits and festive decorations, as well as designs for jewellery, plate, and other precious objects. His portraits of the royal family and nobles are a record of the court in the years when Henry was asserting his supremacy over the Church of England.

Holbein's art was prized from early in his career. French poet and reformer Nicholas Bourbon (the elder) dubbed him "the Apelles of our time", a typical accolade at the time. Holbein has also been described as a great "one-off" in art history since he founded no school. Some of his work was lost after his death, but much was collected and he was recognized among the great portrait masters by the 19th century. Recent exhibitions have also highlighted his versatility. He created designs ranging from intricate jewellery to monumental frescoes.

Holbein's art has sometimes been called realist, since he drew and painted with a rare precision. His portraits were renowned in their time for their likeness, and it is through his eyes that many famous figures of his day are pictured today, such as Erasmus and More. He was never content with outward appearance, however; he embedded layers of symbolism, allusion, and paradox in his art, to the lasting fascination of scholars. In the view of art historian Ellis Waterhouse, his portraiture "remains unsurpassed for sureness and economy of statement, penetration into character, and a combined richness and purity of style."

Hans Holbein the Younger

Self-portrait

1542

Double Portrait of Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve ("The Ambassadors")

1533

Portrait of the Merchant Georg Giese

1532

Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam,

1523

Lais of Corinth,

1526

The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, and a details,

1521–22.

Portrait of Sir Thomas More,

1527

Portrait of the Artist's Family,

c. 1528

Darmstadt Madonna, with donor portraits

1525–26 and 1528

Hans Holbein

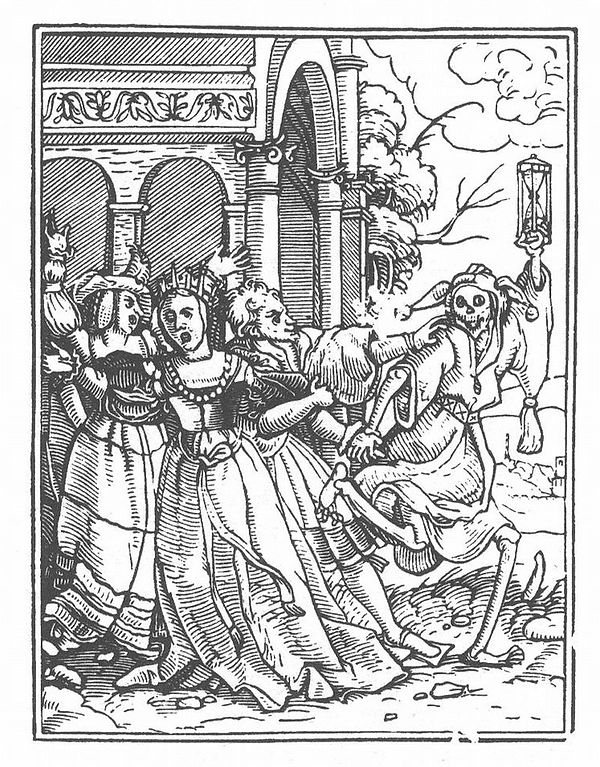

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

The Dance of Death by the German artist Hans Holbein (1497–1543) is a great, grim triumph of Renaissance woodblock printing. In a series of action-packed scenes Death intrudes on the everyday lives of thirty-four people from various levels of society — from pope to physician to ploughman. Death gives each a special treatment: skewering a knight through the midriff with a lance; dragging a duchess by the feet out of her opulent bed; snapping a sailor’s mast in two. Death, the great leveller, lets no one escape. In fact it tends to treat the rich and powerful with extra force. As such the series is a forerunner to the satirical paintings and political cartoons of the eighteenth century and beyond. For example, Death sneaks up behind the judge, who is ignoring a poor man to help a rich one, and snaps his staff, the symbol of his power, in two. A chain around Death’s neck suggests he is taking revenge on corrupt judges on behalf of those they have wrongfully imprisoned. In contrast, Death seems to come to the aid of the poor ploughman, by driving his horses for him and releasing him from a life of toil; the glowing church in the background implies this old man is on his way to heaven.

Holbein drew the woodcuts between 1523 and 1525, while in his twenties and based in the Swiss town of Basel. It would be another decade before he established himself in England, where he painted his most enduring masterpiece The Ambassadors (1533), in which two wealthy, powerful and worldly young men stand above (and oblivious to) an anamorphic skull that signals the ultimate vanity of all that wealth, power and worldliness. In the 1520s, Holbein was busy trying to earn a living in Basel, painting murals and portraits, designing stained glass windows, and illustrating books. The year before he began The Dance, he had illustrated Martin Luther’s influential translation of the New Testament into German. So Holbein was working close to the heart of the accelerating movement for Church reform. It comes as little surprise, then, that Death reserves particularly grim treatment for members of the Catholic clergy. It drags off a fat abbot by his cassock, leads an abbess away by the habit as though she were an animal, and takes the form of two skeletons and two demons to see to the pope himself.

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)

Dance of Death

(1523–1525)