Dadaism - II

Hannah Höch

1889 – 1978

Hannah Höch

(1 November 1889 – 31 May 1978) was a German Dada artist. She is best known for her work of the Weimar period, when she was one of the originators of photomontage. Photomontage, or fotomontage, is a type of collage in which the pasted items are actual photographs, or photographic reproductions pulled from the press and other widely produced media.

Höch's work was intended to dismantle the fable and dichotomy that existed in the concept of the "New Woman": an energetic, professional, and androgynous woman, who is ready to take her place as man's equal. Her interest in the topic was in how the dichotomy was structured, as well as in who structures social roles.

Other key themes in Höch's works were androgyny, political discourse, and shifting gender roles. These themes all interacted to create a feminist discourse surrounding Höch's works, which encouraged the liberation and agency of women during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and continuing through to today.

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch

Man Ray

1890 – 1976

Man Ray

(born Emmanuel Radnitzky; August 27, 1890 – November 18, 1976) was an American visual artist who spent most of his career in Paris. He was a significant contributor to the Dada and Surrealist movements, although his ties to each were informal. He produced major works in a variety of media but considered himself a painter above all. He was best known for his pioneering photography, and was a renowned fashion and portrait photographer. He is also noted for his work with photograms, which he called "rayographs" in reference to himself.

Self-Portrait with Gun

Man Ray

1932

Portrait of Alfred Stieglitz

Man Ray

1913

Departure of Summer

Man Ray

1914

Woman, Man Ray American,1918

Man Ray, c. 1921–1922, Rencontre dans la porte tournante, published on the cover (and page 39) of Der Sturm, Volume 13, Number 3, March 5, 1922

Man Ray, 1919, Seguidilla, airbrushed gouache, pen & ink, pencil, and colored pencil on paperboard, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

3Man Ray, 1919, Seguidilla, airbrushed gouache, pen & ink, pencil, and colored pencil on paperboard, 55.8 × 70.6 cm, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Man Ray, 1920, The Coat-Stand (Porte manteau), reproduced in New York dada (magazine), Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, April 1921

Man Ray, c. 1921–22, Dessin (Drawing), published on page 43 of Der Sturm, Volume 13, Number 3, March 5, 1922

Man Ray, Lampshade, reproduced in 391, n. 13, July 1920

Man Ray, 1922, Untitled Rayograph, gelatin silver photogram

Man Ray, Untitled, rayograph, 1922, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

Man Ray, Planes, 1922, Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA.

Man Ray, Untitled, rayograph, 1922.

Self-Portrait Assemblage

Man Ray

1916

Jazz

Man Ray

1919

The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse

Man Ray

1920

Rrose Selavy alias Marcel Duchamp

Man Ray

1921

The Gift

Man Ray

1921

Portrait of Alfred Stieglitz

Man Ray

1913

Rayograph (The Kiss)

Man Ray

1922

Indestructible Object (or Object to Be Destroyed)

Man Ray

1923

Ingres' Violin

Man Ray

1924

Peggy Guggenheim

Man Ray

1924

Black and white

Man Ray

1926

The Meeting from the portfolio Revolving Doors

Man Ray

1926

Photo De Suzy Solidor, La Fille Aux Cheveux De Lin

Man Ray

1929

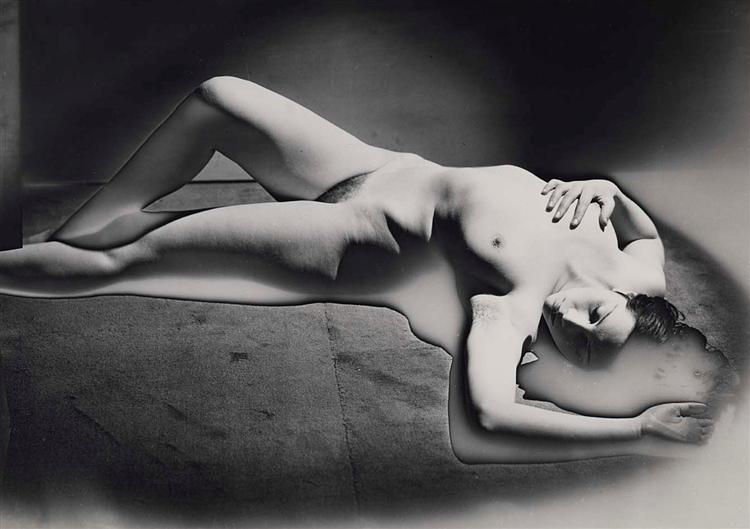

Woman with Long Hair

Man Ray

1929

Primacy of Matter over Thought

Man Ray

1929

Lee Miller

Man Ray

1930

Prayer

Man Ray

1930

André Breton

Man Ray

c.1930

Solarisation

Man Ray

1931

Glass tears

Man Ray

1932

Veiled Erotic Meret Oppenheim

Man Ray

1933

Me, She

Man Ray

1934

Minotaur

Man Ray

1934

Observatory Time: The Lovers

Man Ray

1932 - 1934

The Kiss

Man Ray

1935

Dora Marr

Man Ray

1936

Dora Maar

Man Ray

1936

Pisces

Man Ray

1938

Le Beau Temps

Man Ray

1939

Nut Girls (Les Filles des Noix)

Man Ray

1941

Self-Portrait

Man Ray

1941

Shakespearean Equation: Twelfth Night

Man Ray

1948

The Imaginary Portrait of the Marquis de Sade

Man Ray

Lee Miller

Man Ray

Portrait of Alfred Stieglitz

Man Ray

1913

Self-Portrait

Man Ray

Max Ernst

1891 – 1976

Self-portrait

Max Ernst

1909

Max Ernst

(2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976) was a German (naturalised American in 1948 and French in 1958) painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and Surrealism in Europe. He had no formal artistic training, but his experimental attitude toward the making of art resulted in his invention of frottage—a technique that uses pencil rubbings of textured objects and relief surfaces to create images—and grattage, an analogous technique in which paint is scraped across canvas to reveal the imprints of the objects placed beneath. Ernst is noted for his unconventional drawing methods as well as for creating novels and pamphlets using the method of collages. He served as a soldier for four years during World War I, and this experience left him shocked, traumatised and critical of the modern world. During World War II he was designated an "undesirable foreigner" while living in France. He died in Paris on 1 April 1976.

Luise Straus with her Dadaist friends: (from left to right) Emil Nolde, Max Ernst, Richard Straus and Johannes Theodor Baargeld. 1919

The end of the war, in which Germany was defeated, was marked by a significant event in the life of a young and still wavering artist from the suburbs of Cologne: Max Ernst married Luise Straus — a well-educated and successful art historian.

Luise Straus-Ernst (December 2, 1893 – d. early July 1944), also known as Louise Ernst, Louise Straus, Louise Ernst-Straus, or Luise Ernst-Straus, was a Jewish German art historian, writer, journalist, and artist, sometimes using an artistic Dadaist alias Armada von Duldgedalzen.

She was the first wife of surrealist painter and sculptor Max Ernst and mother of painter Jimmy Ernst.[1]

Being a Jew, when the Nazis came to power, she emigrated to France in 1933. With the outbreak of World War II she could not emigrate further and found refuge in a hotel in Manosque, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France, together with a group of other Jewish emigrants. There she wrote her autobiography Nomadengut. The manuscript survived and was published in 2000. On April 28, 1944 she was arrested in a raid and on June 30 deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp, where she was killed on an unknown date.

Surrealist Max Ernst was involved in a polygamous relationship with Elena Ivanovna, aka Gala Dalí, and Paul Éluard. Here he is on the day of his joint marriage with his wife Dorothea Tanning, Man Ray and Juliet P. Browner.

Max Ernst, Gala and Paul Éluard. Photo from 1922

In the autumn of the same year, the Éluards visited the Ernsts in Cologne. That time, the stars were aligned. Éluard and Ernst became each other’s sources of inspiration — the deep, bottomless and vibrant ones. In March 1922, there was published Répétitions — a collection of Éluard's poems and Ernst’s collages. Close relations between Ernst and the Éluard's turned into a love triangle. Gala didn’t hide anything from Éluard, who responded to all the assaults saying: "I love Max Ernst much more than Gala does."

Max Ernst his son Jimmy, Gala and Paul Éluard with their daughter Cécile and Luise Straus-Ernst. Innsbruck, 1922

Gala Dali

Max Ernst

1924,

Luise Straus-Ernst with her son Jimmy. 1928

Absolute peace reigned among that strange trio. Except that Luise Straus didn’t want to accept that: she took her son and left Ernst with Gala. Officially, their marriage was dissolved in 1926.

Marie-Berthe Aurenche, Max Ernst, Lee Miller, and Man Ray, 1932

In the autumn of the same year, in one of the art galleries, he met a young daughter of a high-ranking official, Marie-Berthe Aurenche. They were introduced to each other by Marie-Berthe's brother, director Jean Aurenche, who would win three César awards in the future and who was close with many Parisian artists. The beautiful Marie-Berthe, or, as she was called, Ma-Be, became Ernst’s beloved wife; their marriage lasted ten years.

Max Ernst & His Wife, Marie-berthe Aurenche, 1930. Photo from the Man Ray Trust

A French aristocrat of ancient lineage, educated by the nuns of the Faithful Companions of Jesus, Marie-Berthe was mesmerized by a German artist whose popularity had just started to gain momentum. Having found out about their relationship, the girl’s father went to the police and accused Ernst of corrupting a minor. The lovers fled and had to hide for several months; Ernst sent letters to the bride’s father, begging him to give consent to their marriage. The couple married in 1927 and settled on the south-western outskirts of Paris. Two years later, Max Ernst created another graphic novel — The Hundred Headless Woman with a foreword by André Breton. In the book there was Gala, Marie-Berthe, and Loplop, "the Bird Superior," one of Ernst’s favourite fantasy characters.

Meanwhile, Marie-Berthe's eccentric excesses which Ernst considered amusing at the beginning of their married life, gradually became unbearable to him. In 1936, Ernst’s marriage with Marie-Berthe Aurenche broke up. Ma-Be turned to Catholicism, vainly hoping to bring her beloved man back by prayers and pilgrimage. Just for the record, in 1940 Ma-Be became the last woman in the life of the artist Chaïm Soutine.

Max Ernst, Leonora Carrington, Marcel Duchamp and André Breton

Delighted, enraptured and enamoured, Leonora left her studies at the Royal Academy of Arts in London and moved to Paris. "I fell in love with Max’s paintings before I fell in love with Max," Leonora later recalled. Carried away by creativity, a lovely company of surrealists helped her and Max resist the horrors of fascism, which by then began to creep across Europe.

Leonora in the Morning Light

Max Ernst

Max Ernst and Leonora Carrington. Photo from 1937

The Second World War began, and Max Ernst, as a German national, was sent to the internment camp, from which he was rescued by Paul Éluard, having clout in the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Leonora Carrington, experiencing those events all by herself, had a nervous breakdown and was taken to Spain by her friends. After the second breakdown, Leonora’s father insisted on her treatment in a psychiatric clinic, where she fled from in 1941. Having applied for political asylum in the Mexican Embassy, Leonora found the opportunity to leave Spain by contracting a fictitious marriage, crossed the Atlantic and arrived in Portugal, later moving to the United States.

Leonora Carrington finished her escape from the horrors of Nazism in Mexico. There she found a family, gave birth to two sons and lived a long and fruitful life. Without Max. Leonora Carrington’s work is considered a national treasure in Mexico.

Max Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim. Photo from the early 1940s

Max Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim got married in December 1941.

They settled in a mansion on the East River, where Ernst had a large and comfortable studio. Peggy was one of the richest women in the world, who helped many artists fleeing the war and finding themselves in America on a shoestring. Yet, despite the creative atmosphere prevailing in their house, the marriage of Peggy and Max was quite short.

Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning (1942, photo by Irving Penn)

And in 1943 Ernst met a young artist — Dorothea Tanning. They say that it was Peggy who asked her husband to evaluate a painting of the young artist, who boldly and catchily depicted herself in a self-portrait. And Ernst turned out to be fascinated by the original.

A Swede by origin, Dorothea came to Chicago in 1930 to study painting. A few years later, having visited the exhibition of Surrealists and Dadaists, she fell in love with new art and became deeply engrossed in it. Having moved to New York, Dorothea joined André Breton’s Surrealist group, and a year later met Max Ernst. After a three-year relationship, Ernst and Tanning got married in Hollywood.

Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. Photo by Lee Miller

Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. Sedona. Arizona. Photo by Lee Miller

Carrington and Max Ernst. She rejected male Surrealists’ views of women.

Photograph by Lee Miller /Lee Miller Archives, England

Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst

Max Ernst, Leonora Carrington, and Lee Miller

Paul Eluard, Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst at Lambe Creek. Photographed by Lee Miller

Leonora Carrington, André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, and Max Ernst, New York City, 1942; photograph by Hermann Landshoff. At center is Morris Hirshfield’s painting Nude at the Window (1941).

A magnificent bird. Portrait of Max Ernst

Leonora Carrington

1939

Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning.

Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning.

Max in a blue boat

Dorothea Tanning

MAX ERNST:

THE HAT MAKES THE MAN. 1920. New York. MOMA

Le Limaçon de chambre

1920

The Gramineous Bicycle Garnished with Bells the Dappled Fire Damps and the Echinoderms Bending the Spine to Look for Caresses

1920

Un peu malade le cheval patte pelu...

1920

Family Excursions

1919

Stratified Rocks, nature's gift of gneiss iceland moss 2 kinds of lungwort 2 kinds of ruptures

of the perineum growths of the heart (b) the same thing in a well-polished box somewhat more expensive

1920

Katharina ondulata 1920

Untitled.

1920

Untitled.

1920

MAX ERNST: AU RENDEZ-VOUS DES AMIS. 1922. Cologne. Wallraf-Richartz Muséum

Au rendez-vous des amis, 1922: Aragon, Breton, Baargeld, De Chirico, Eluard, Desnos, Soupault, Dostoyevsky, Paulhan, Perst, Arp, Ernst, Morise, Fraenkel, Raphael, 1922

MAX ERNST: AU RENDEZ-VOUS DES AMIS. 1922. Cologne. Wallraf-Richartz Muséum

Au rendez-vous des amis, 1922: Aragon, Breton, Baargeld, De Chirico, Eluard, Desnos, Soupault, Dostoyevsky, Paulhan, Perst, Arp, Ernst, Morise, Fraenkel, Raphael, 1922

MAX ERNST:

THE ELEPHANT OF CELEBES. 1921.

London. Tate Galle

Max Ernst: Ubu Imperator. 1923

Fruit of a Long Experience 1919

People know nothing

Max Ernst

1923

The Song of the Flesh 1921

Oedipus Rex 1922

The Equivocal Woman (The Teetering Woman) 1923

Woman, Old Man and Flower 1923

Two Children are Threatened by a Nightingale 1924

Castor and Pollution 1923

Max_Ernst ~The_temptation_of_St_Anthony

The Couple or The Couple in Lace 1925

Max Ernst. At the First Limpid Word

Au premier mot limpide

1923

Max Ernst. The Virgin Spanking the Christ Child before Three Witnesses: Andre Breton, Paul Eluard, and the Painter, 1926

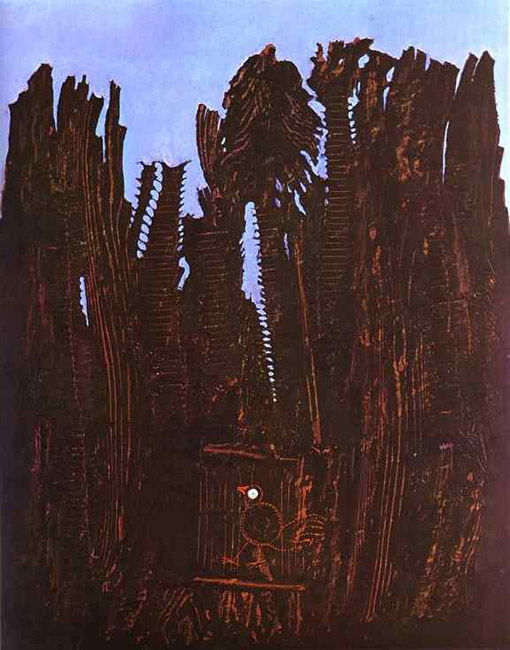

Max Ernst. Forest and Dove. 1927

Max Ernst. Fishbone Forest 1927

Max Ernst. After Us Motherhood 1927

Max Ernst. The Virgin Spanking the Christ Child before Three Witnesses: Andre Breton, Paul Eluard and the artist

1928

Max Ernst. Paysage coquillages 1928

Max Ernst. Die Erwahlte des Bosen. 1928

MAX ERNST: EUROPE AFTER THE RAIN, II. 1940-1942. Hartford. Atheneum Museum

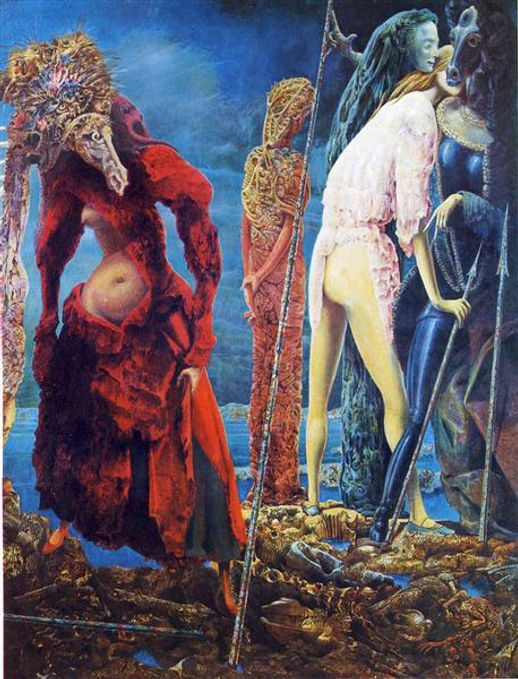

The Angel of the home or the Triumph of Surrealism

Max Ernst

1937

Barbarians

Max Ernst

1937

The Spanish Physician

Max Ernst

1940

Epiphany

Max Ernst

1940

Marlene (Mother and son)

Max Ernst

1940

Napoleon in the Wilderness

Max Ernst

1941

Surrealism and Painting

Max Ernst

1942

The Antipope

Max Ernst

1942

The King Playing with the Queen

Max Ernst

1944

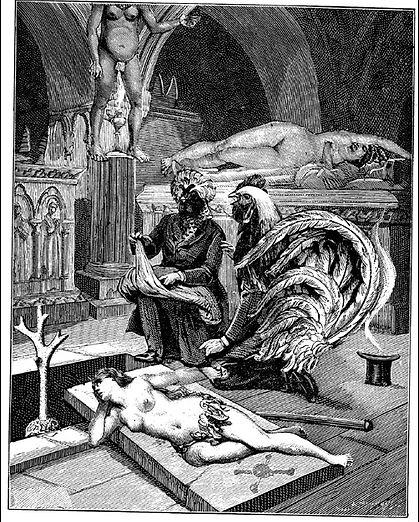

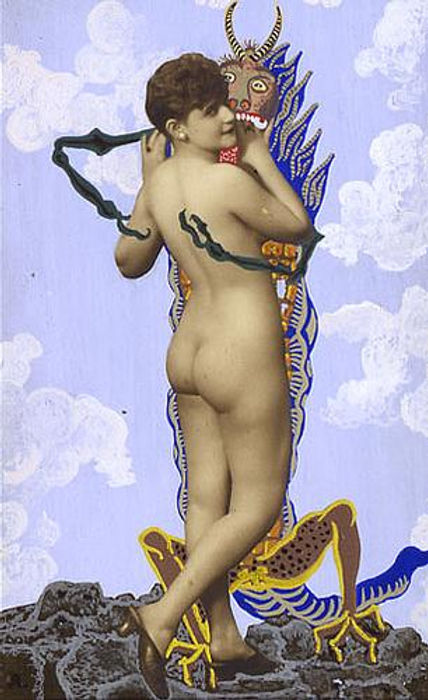

Max Ernst: "The Hundred-Headless Woman"

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

.jpg)

* * *

.jpg)

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

.jpg)

* * *

* * *

* * *

Max Ernst: A Little Girl Dreams Of Taking The Veil

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

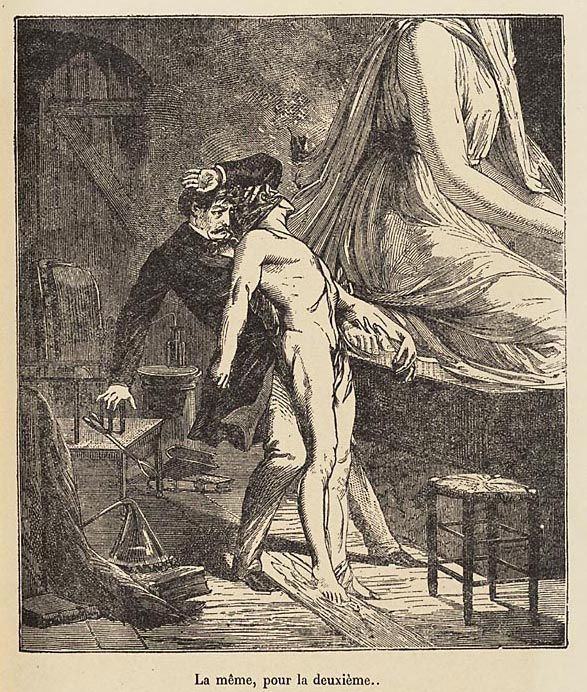

Max Ernst

"A Week of Kindness"

(A surrealistic novel in collage)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

.jpg)

*

.jpg)

*

.jpg)

*

.jpg)

*

.jpg)

.jpg)

*

*

*

Georges Hugnet

1906 – 1974

Georges Hugnet

(11 July 1906 – 26 June 1974) was a French graphic artist. He was also active as a poet, writer, art historian, bookbinding designer, critic and film director. Hugnet was a figure in the Dada movement and Surrealism. He was the author of the collage novel Le septième face du dé (1936).

Hugnet wrote about the "Exposition surrealiste internationale", saying "Les artistes surrealists ... se sensetaient tous l'ame de Pygmalion ... On put voir les heureux posseurs de mannequins...arrive. munis de mysterieux petits ou grands paquets, hommages a leurs bien-aimees, contenant les cadeaux les plus disaparates." Lewis Kachur translates this as "The Surrealist artists all felt they had the soul of Pygmalion. One could see the happy owners of mannequins ... come in, furnished with mysterious little or big bundles, tokens for their beloved, containing the most unlikely presents."

There is an inventory of his papers in the Carlton Lake Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center of the University of Texas at Austin.

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet

Georges Hugnet